Distance

In the whirlwind of depressive events that the covid 19 epidemic has forced upon us, one of the worst situations we are called upon to deal with is interpersonal distancing. I prefer this term to “social distance.” The latter calls to mind the difference between social classes and therefore I don’t think it is quite correct. Social distance existed even before the advent of the virus in question. The “detachment” to which this pathogen forces us, instead, is completely individual, even if it is transversal among the strata of society. Therefore, the physical distance imposed by the vituperative germ is a serious vulnus because it puts out of play one of the most fundamental needs of the human being: contact.

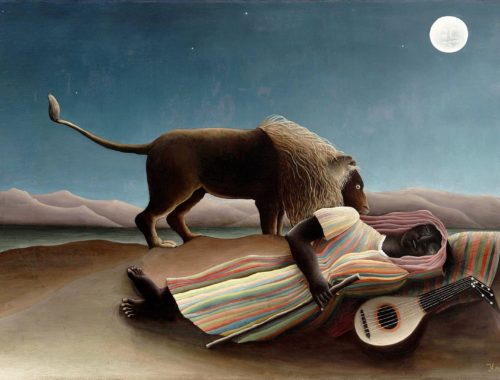

We know from studies in child psychology that the first and most important of the senses involved at birth is touch. Today, after a long period of latency, this knowledge has finally been completely absorbed by modern Italian obstetrics and, at birth, the baby with the umbilical cord still healthy is placed on the bare belly of the mother. The epidermal contact with the consistency of the maternal body, with its warmth, with its smooth surface is an imprinting so strong that we find it throughout the course of our lives. The reassuring embrace of the mother, her tender kisses, her affectionate caresses will be the incessant search for love in each of us throughout our lives.

Physical contact is so important that in some psychotherapeutic techniques, strictly codified by strict rules, it is provided and used for beneficial and healing purposes, even from depressive and melancholic states. The importance of contact is found in many liturgies, including the Catholic one when the priest, in church, invites to exchange a sign of peace. Therefore, even in the light of these few simple explanations, it is easy to understand why the blow that covid 19 has dealt to the whole of humanity is hard and deep.

The inevitable constraints resulting from this prophylactic necessity blow up the habits of encounter that are the salt of every person’s life. Man is a social being and, as a rule, needs the presence of others because it is through the recognition of his neighbor that he receives a strong confirmation of his ego. Paradoxically, at the same time, the individual needs his privacy and, therefore, the possibility of being able to retreat into a more isolated dimension of intimacy. Woe if he could not have this eventuality.

The imposition of being relegated to a restricted place, without the possibility of interrupting his state of withdrawal, is not by chance one of the heaviest punishments, depending on the duration, that even the judicial system imposes. The shortage of contacts, the distance from those who love us and whom we love, is a condition that can easily cause us to slip into a state of depression, and even exacerbate non-obvious forms of mental illness. We are witnessing, in this prolonged lock down, a resurgence of acts of violence, even directed against one’s own person. Not least the revolts of groups that do not accept the prolonged constraint of their freedoms. With the closure of distance learning, we see masses of pre-adolescents who meet via social media only to confront and beat each other up. Many naively wonder where this urgency for violence comes from. The explanation is simple. Contact with others is so important and decisive for the confirmation of one’s ego that even a violent gesture is preferable to emptiness and absence. A caress and a kiss are the best; the slap and the kick, however, are preferable to the indifference that makes us invisible to ourselves and to the world. In a novella by Edgar Allan Poe, The Man in the Crowd, terror runs along the lines of the shocking anxiety a man feels at the mere idea of not being able to have physical and visual contact with his fellow man. The paroxysmal increase in anguish goes hand in hand with the arrival of night, a period in which contacts and sightings inevitably decrease.

Even the nostalgia of the emigrant can be explained through the realization of how vital it is for everyone to have closeness with those who love us or, at least, recognize us. Living in a foreign country by necessity, where no one, especially at first, will speak to you because you are neither known nor recognized (an invisible person, perhaps the worst nightmare you can dream of), opens an irremediable and unspeakable psychic wound that makes you look back to the things you love, to the people you love most, to the land of origin, the motherland from whose rites and forms of participation you draw the lifeblood and strength to live.

The migrant’s delusional psychiatric bouffèe (TBP) is a psychic phenomenon well known in countries with strong immigration. In the light of these brief considerations, however, it is soon clear that ethnic groups need to meet, periodically in fixed places and at fixed times, in foreign host cities. Even the rise of neighborhoods called, for example, Little Italy or Chinatown is easy to understand at this point.

Scholars of paleoanthropology (Prof. David Caramelli of Florence University for example) have assumed an alternative hypothesis regarding the extinction of Neanderthal, in addition to that of hybridization or climatic disaster (eruption of the megavolcano Toba). We know that the phylogenetic development of human being is not to be considered longitudinal causal, but stochastic, that is, circular random. At the same time on the planet lived many human species (some scholars declaim them as subspecies) such as Homo neanderthalensis, precisely, that according to some genetic paleontologists shared 99.5% to 99.9% of DNA heritage with Homo sapiens. (Edward Rubin of Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory). Other types of Homo existed at the same time as Sapiens, “human” realities that some scientists do not feel comfortable calling its subspecies, in agreement with many colleagues who prefer the term species. Homo idaltu; Homo heidelbergensis; Homo neanderthalensis; Desinova’s Homo; The study of paleoanthropology makes us understand how the power of Man is determined by collectivity. Abstract thinking (leading to the symbolic and logical mathematical) in all probability has been the “strength” of Sapiens. This intellectual characteristic led him to gather in large communities precisely to follow his need for symbolism and the transcendent.

The religious animistic liturgies are traced in numerous testimonies found in artifacts, remains of bones, cave paintings, etc. The other human beings contemporaries of Sapiens probably, even if they were skilled and with excellent skills of adaptation to the environment, they did not have much developed this capacity of thought. Therefore, they gathered in non-large families.

The Sapiens, although weak in many ways as a living being, was able to overcome the challenge of survival because it gathered in large communities and, consequently, through liturgical codifications, cooperated better than any of its similar or different animals on Earth. The secret of its success was and still is its ability to make community. In community, contact, the oppositional principle par excellence of distance or remoteness, is everything. I do not believe in the peaceful evolution of mankind. The competition for survival must have been very hard, against nature and against similar claimants to the same resources. The modern Sapiens, as we understand it today, has coexisted with many of his kindred, but has won the challenge of non-extinction by literally slaughtering all other “humans” his contemporaries. The proximity, the contact, the staying together with codified rituals producing hierarchies and social tasks has been its real strength. In our days, for us descendants, remains the same enormous need to be able to carry out this characteristic of proximity, of meeting, of being in presence in the community without which we are prey to ancestral fears because, then as now, being isolated means greater vulnerability or even death.

This is why interpersonal distance, to which the covid 19 epidemic has condemned us for many months now, produces such negative effects on the psyche that we react with intolerance, explosions of violence or even depression.

La lontananza

Padre nostro...

Potrebbe anche piacerti

Professione: Operatrice D’infanzia

30 Aprile 2020

La fontana dell’esedra

18 Febbraio 2021